Two days ago I posted a lengthy article about the photo gear I took to Turkey. But I was still curious which lens(es) I might have been able to do without if I had to do it all over again. To be objective I logged the EXIF data to see the focal lengths of the first 94 images I published from the trip (out of 4,200 taken). They’re a good sample and generally the best of what I shot. Below is a chart showing the results.

This is a histogram/scatter chart. (Thanks to Ian Leslie for his suggestion of a better way to display these data.) Click to enlarge it. The vertical scale is focal length (logarithmic). The bottom is 10mm and the top is 200mm. There’s no horizontal scale, just 94 horizontal positions, one for each photograph. So just consider the height of the blue diamonds and how they cluster. I added two horizontal red lines to highlight the two prime lenses: 24mm and 50mm. And on the right side there are two vertical lines showing the ranges of the two zooms.

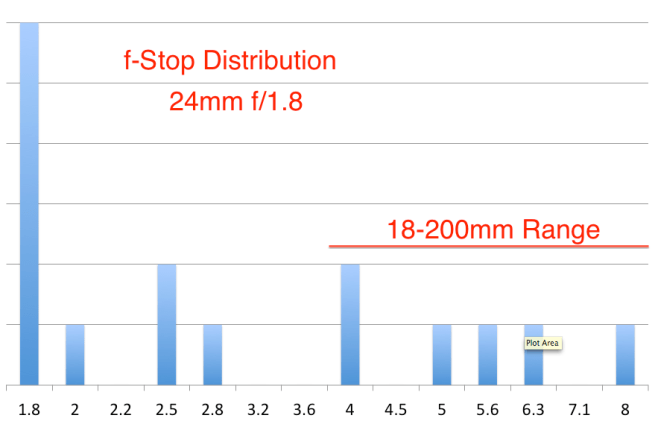

I used four lenses, the ranges of which are shown above in red:

- 24mm f/1.8

- 50mm f/1.8

- 10-18mm f/4

- 18-200mm f/3.5-6.3

So what conclusions can I draw? As I expected, the 24mm was more valuable than the 50mm. But if I hadn’t had the 10-18mm or the 18-200mm, there are a lot of shots that wouldn’t have been captured, at least not the same way. From this chart, I don’t see anything that would convince me to change the lenses for the next trip, but it was an interesting experiment nonetheless.