This is one of those too-much-information (TMI) posts. I spent most of October 2011 in the hospital due to a liver abscess and subsequent complications, but due to my condition and medications I remember very few details of what happened during that time. I’ve reconstructed the following chronology based on notes taken by, and discussions with my wife, son, sisters and doctors. I wrote this primarily for myself, so I’d have a better understanding of the events. Warning: I don’t expect it will be of much general interest. And it’s long!

October 1-2

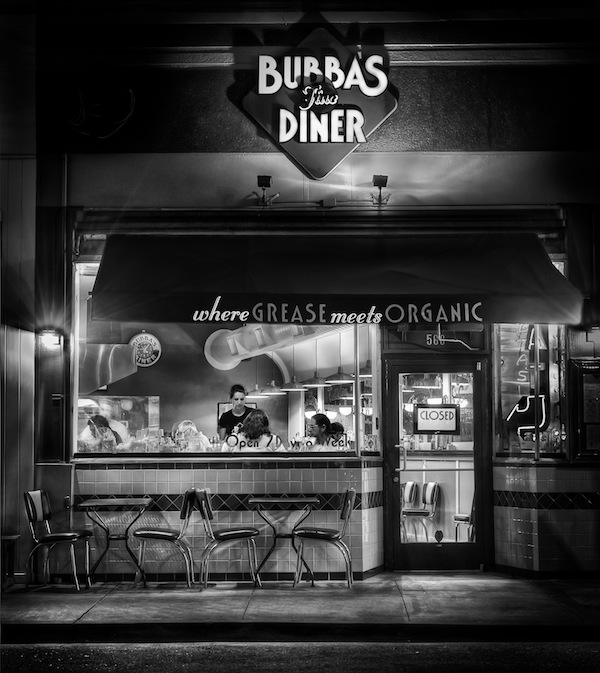

The last week of September 2011 was filled with photography: two photowalks with Google+ friends in Santa Cruz and Half Moon Bay; a third in Golden Gate Park with a group from the Marin Photo Club; and a long afternoon/evening private shoot on Alcatraz with Joe McNally. I was also scheduled to co-lead one of the Worldwide Photowalks with Catherine Hall in San Francisco on Sunday, October 2.

But on Friday it all caught up with me. I was wiped out and felt like I had really done too much. As the day progressed, I felt worse and worse. I knew something was seriously wrong. I had only a slight fever, but the shivers and shakes were severe. I was producing very little urine, and what I did produce was extremely dark brown. Uh-oh, I thought: There’s a problem with my kidneys.

At 3am on Saturday October 1, I called the advice nurse at Kaiser Permanente, our HMO. She asked the appropriate questions and said she’d discuss my symptoms with an M.D. on duty. The advice nurse called back and told me to head to the lab for some blood tests as soon as they opened that morning. My wife had her own health issues (retinal bleeding) and couldn’t drive, so I drove myself to the lab, had the tests and drove home. Within two hours I got a call from the doctor who told me I should come in to see her ASAP and to plan on heading directly to the emergency room from there.

I drove myself to the ER, which probably wasn’t too smart. My wife rode with me, but I think it was a bit of a wild ride. In the ER I was quickly put on IV saline and given lots of tests: a chest x-ray showed some pneumonia; there were kidney problems and bowel problems. (The first doctor was concerned about a possible bowel obstruction.) Finally a CT scan showed a mass “the size of a large grapefruit” in my liver. They didn’t know what it was, but the possibilities included a malignant or benign tumor or an abscess. The only way to tell would be a biopsy, and since it was now Saturday night and the procedure couldn’t be done until Monday morning, I was admitted to the hospital and waited 36 hours. My fever was up to 103.4.

October 3

Monday morning they wheeled me down to a department I’d never heard of: Interventional Radiation, where a team of doctors and assistants perform surgical procedures with the aid of live x-rays, fluoroscopy, etc. It’s pretty wild. There’s a lot of hardware and computer-enhanced imaging and the team members are all wearing lead coverings. They inserted a large needle into my liver. I was quite sedated, but I do remember the point at which one of the doctors said, “We’re getting pus,” or something like that. I realized that was good news. It was an abscess, not a tumor. They drained some of the fluid and inserted a drain tube, which I kept for the next four weeks. They never did perform a biopsy of the liver itself.

It was getting harder and harder to find veins for IVs, so somewhere along the line — I think it was this day — a nurse inserted a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line into my left arm. This is a catheter in the vein that runs up the arm, across the chest and into the vena cava. It’s not as creepy as it sounds. Now I had two ports that could be used for IV medications and even blood draws without having to poke a new vein each time.

I spent the rest of the day in a recovery room, but I was getting sicker and sicker by the hour, so they moved me to the intensive care unit (ICU). The pain in my abdomen was now excruciating when I breathed. I had developed a pleural effusion in my right lung. My breathing was faltering and my arterial blood gases weren’t good. I became acutely septic. In other words, I was one very sick puppy.

They started respiration therapy and told my wife if I couldn’t breathe more deeply they would have to put me on a ventilator. I was holding my breath to avoid the pain, but apparently no one understood that. I wasn’t able to communicate because I was just too out of it. Finally a nurse figured it out, got me started on continuous morphine — it apparently took quite a bit — and she and my wife talked me into exhaling instead of holding my breath. Ventilator avoided.

The good news at this point was I didn’t have liver cancer. The bad news was I was going downhill fast from a bacterial infection in my bloodstream and messed up blood gases due to my poor breathing.

In the meantime, the labs identified the primary/original culprit: a bacterium known as Streptococcus milleri. This bacterium is one of those that we all have in our mouths, stomachs and intestines, but if it gets into our bloodstreams it’s extremely toxic. Normally the liver can deal with small amounts of milleri, but in my case there was way too much and the liver was overwhelmed. Rather than filter it, as the liver normally does, it created a separate space (the abscess) where it kept the infection segregated. Because of the size of the abscess, the infectious-disease specialists thought this process had been going on for four to six months. They started an IV antibiotic that was specifically targeted to Streptococcus milleri.

October 4

Tuesday the doctors were worried I was developing Acute Respiration Distress Syndrome (ARDS), which along with the acute sepsis was a potentially fatal condition. I had pneumonia, but they weren’t too worried about that since the antibiotics should be taking care of it. I also had serious edema. I had gained 25 pounds of fluids since this whole thing started.

October 5

The next morning my team decided to perform a thoracentesis. Using local anesthetic, they inserted a needle below my right shoulder blade into the pleural cavity around my lung to remove some of the fluid that had accumulated there. They removed 200-250cc of fluid, but another x-ray revealed 600-700cc — two-thirds of a litre! — remained. At this point I was getting a chest x-ray at least once every day, which continued until my last day in the hospital. The fluid they removed was more similar to the fluid from the liver than the doctors liked. They told me it was not uncommon for the infection and fluid from a live abscess to reach the lung, sometimes via a “tunnel”. The liver is just under the right side of the diaphragm, which is why it had become so painful to breathe. The doctors increased my pain medication again.

October 6

By Thursday the size of the liver abscess was dramatically smaller. My fever subsided and my blood gases and blood pressure, which had been very low, returned to normal. In the afternoon, after three days in the ICU, I was transferred to a regular floor. But the doctors continued to drain more fluid from my pleural cavity. The subject of thoracic surgery was raised, but only if the abscess “shelled” out from the liver or the fluid in my lungs developed into too many separate “pockets” such that it couldn’t be easily drained.

Unfortunately, I developed swelling in my left arm and an ultrasound revealed I had developed a blood clot — an acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT) — from the PICC line. I was immediately started on Heparin to thin my blood and reduce further clotting.

October 7-9

Over the next three days my condition improved steadily. I still had a lot of tubes including an IV (saline, two antibiotics, pain meds, diuretic), an arterial catheter (to track blood gasses), the liver drain and the IV PICC line, but with the help of the physical therapists I was finally able to get out of bed (to use the bathroom instead of a bedpan!) and to walk. At first it was just a few steps but by Sunday I was able to climb twenty steps, a requirement for going home.

But the hospital is a quiet place on weekends. A number of departments have minimal staff on Saturday and Sunday and in general it seems procedures and decisions tend to be delayed until the start of the week when the full team returns.

October 10

On Monday things got busy once again. It started with another CT scan, which unfortunately showed more fluid was accumulating in the pleural effusion, which had also become loculated — split into a number of those separate pockets. This meant they couldn’t be reasonably reached with further thoracentesis, so the only solution was thoracic surgery, and for that I’d have to be transported to the larger hospital in San Francisco. Furthermore, the original liver abscess wasn’t resolving as quickly as the doctors had hoped. It hadn’t changed in size since the previous CT scan. To make matters worse, I now had several small blood clots, which could be new or could have broken off from the original one. These would need to be watched.

The medical-transport crew arrived like a SWAT team of paramedics. With a drill-sargent nurse as their crew chief, they whisked me off by ambulance to San Francisco. Once there, the PICC line in my left arm was removed and replaced with a new one in my right arm.

October 11

Tuesday was thoracic surgery day. I learned they would make multiple relatively small incisions and use a camera and tools to remove the material of the pleural effusion. There was a 20% chance it might be worse and they’d have to perform a more complex procedure with a lot more cutting. (That didn’t happen, thank goodness!) Post-op there was some chance of scarring of the lungs and that I could lose 10-20% of my lung capacity.

I woke up after the surgery in the cardiovascular (CV) ICU in a lot of pain and with some new tubes: a catheter in my bladder and drain tubes in my chest. I still had the liver drain as well. To make matters worse, there was a mixup on my pain medication and I was without it for many hours. Of the times I can remember, this was the worst for me. Finally they gave me IV Dilaudid (synthetic morphine) and things calmed down.

October 12

Recovering from the surgery, was tough. Again, this may be because I was also becoming more coherent and aware than I had been for the first eleven days of this ordeal. I was still in the CV ICU. My edema had become quite serious, but the diuretic (Lasix) was finally kicking in. My blood pressure reached 215/145, and it could only be measured on my legs because I had a clot in one arm and the PICC line in the other.

October 13

Thursday was more of the same, but I was stable so they moved me out of the CV ICU to a CV post-surgery floor. This is also pretty much the first day I can remember. Except for the day just prior to surgery, the first twelve days are still pretty much a blur to me at best. I think it’s a combination of medication and the body’s reaction to the infection, procedures, etc.

Along with full consciousness came real discomfort. I still had serious edema. My feet looked like bloated potatoes. My body temperature swung back and forth between cold chills and hot sweats, which was a bigger problem than it might sound. The pain was weird. It was never acute. In fact, it took me a while to realize it was actually pain because it was so non-specific. All I knew was that I was extremely uncomfortable and the only solution was narcotics. After surgery I was given an intravenous Patient Controlled Analgesia (PCA) device. You get a button you can press to get an immediate small dose of Dilaudid, then it’s locked out for some period of time like 10 or 20 minutes. I also had oral narcotics (Norco/Vicodin and Percocet) but these took 45 minutes or more to work. (Actually, the Percocet just made me stupid. It didn’t seem to do anything for the pain.) The PCA was great when the pain broke through the other drugs and I couldn’t wait until the next oral dose took effect. Unfortunately, I worked hard to use it as little as possible, so they took it away! That will teach me. I guess if I’d pressed the button a few times an hour they might have thought I needed it longer.

My other error had to do with food. The regular menu was decent, but they had to test my blood sugar before every meal and possibly give me a somewhat painful insulin injection depending on the results. I’m not diabetic, but I guess the blood sugar/insulin relationship frequently gets weird after surgery like mine. So I made a deal with one of my doctors. I said I’d be willing to eat the diabetic menu if I could stop getting the tests and injections. Big mistake! Whatever you’ve heard about hospital food, there’s nothing as bad as the food they serve to diabetics. I don’t really how to describe it other than to say it has no flavor whatsoever. And of course there’s nothing interesting on the plate to begin with.

October 14

The main event Friday was a transesophageal echocardiogram. From the time of the original diagnosis, the infections-disease doctors were concerned about my heart. Streptococcus milleri often causes endocarditis, an infection of the heart valves. The test sequence for this is rather strange. First they perform a non-invasive (ie, from outside the chest) ultrasound transthoracic echocardiogram. If the results are negative — ie, they don’t detect any endocarditis, as was my case — then they perform the more invasive transesophageal echocardiogram. This is one of those procedures where you have to swallow an ultrasound transducer to get it into your esophagus, which positions it close to the heart valves so the radiologists can get a very clear picture. As with some of these other procedures, it wasn’t as bad as it sounds. My results were thankfully negative for so-called vegetation on the valves.

But I was still quite uncomfortable. I wasn’t allowed to get out of bed on my own until I had the approval of the physical therapist. I had six different IV drip bags feeding the two ports in my PICC line: saline, two antibiotics, blood-pressure medication, pain medication and the diuretic. But for the first time since the earliest days in the emergency room, they removed the supplemental oxygen I’d been breathing. And with the help of the pain medication, I finally got a good night’s sleep.

October 15-16

Finally, on Saturday, the doctors began talking about my going home. Each department had their own requirements for my discharge. The surgeons wanted my chest drainage to stop. They discontinued the active (vacuum) suction and let gravity take over. Other MDs were still concerned about the known DVT (blood clot) in my left arm and possibly one in the right arm, so I was wheeled down to radiology for another set of ultrasounds. The left arm clot was smaller and there was no sign of one in the right. Regardless, they told me I’d be on steady Heparin until my release form the hospital, then three months of Warfarin (coumadin) at home. I was also still receiving intravenous antibiotics (Ceftriaxone) for the original liver infection, which would also be continued after my discharge. As before the lung surgery, physical therapy wanted to make sure I could get in and out of bed on my own and walk up and down stairs. The bed was still a challenge, but I was able to walk about 1,000 feet and climb 24 steps. My edema was still a problem, so the IV Lasix continued.

I was feeling better and getting stronger every day, but still had a lot of pain from the surgery. The pain had shifted from the incisions to my ribs. The surgeon explained that they had to spread the ribs, tweak some muscles and stretch the cartilage to do what they needed to do, hence the pain I was feeling.

Like I said before, not much happens on weekends, so Sunday was just another day of waiting, trying to control the chills, sweats and pain, and wishing I hadn’t opted for that diabetic menu. On occasion I was able to talk a technician or food server into giving me something I wasn’t supposed to have. I was desperate for anything with flavor.

October 17

Monday morning the first string returned to work and I was able to get the procedures and tests I needed to wrap things up. The most significant was another visit to the Interventional Radiation department to check and reposition the drain in my liver, since that one was going to stay in even after I went home.

October 18

After 17 nights in two hospitals, I was finally discharged. At the very last minute, a physician’s assistant from the surgery department came and removed my chest tubes. Just like he said, it hurt slightly for about three seconds and then it was done.

Because of the long wait through the weekend, I was fairly strong and stable on my feet. Physical therapy had given me a cane, but I no longer needed it. I could walk up and down a full flight of stairs, and while it was a bit awkward and painful, I could get into and out of bed on my own.

I went home with a fair amount of paraphernalia and medications including:

- the PICC line in my right arm so I could self-administer intravenous drugs and get blood tests without another needle in my vein each time;

- a “JP” drain in my liver with an external suction pouch, which I safety-pinned to my clothing;

- lots of bandages over about eight incisions and other wounds from various procedures;

- intravenous Ceftriaxone (Rocephin), an antibiotic to kill off any remaining Streptococcus milleri;

- Metronidazole (Flagyl), another antibiotic to fight an amoebic infection they thought I could have. I was still taking it because a few weeks were required to get the results of the lab tests I had early on;

- Warfain (coumadin) for the potential and known blood clots; and

- Lisinopril for my blood pressure which had become higher than normal during my hospitalization.

Recovery

Once home, my recovery progressed quite rapidly. My wife, a retired R.N., changed my dressings. Kaiser has an amazing Home Infusion service, which delivered and monitored my IV antibiotics. I went frequently to the local outpatient infusion center for blood tests and PICC-line dressing changes. After about three weeks, I ended the antibiotics and the PICC was line removed.

On November 1 I returned to the Interventional Radiation department in San Francisco. It was supposed to be another “drain check” procedure, but they removed the liver drain altogether without me even knowing it. Never felt a thing.

Because of the DVTs (blood clots) I’m still taking Warfarin daily and getting blood tests once or twice a week to monitor the clotting times. This should end in early January 2012.

I’ve also been getting chest x-rays nearly once a week. I still have a pleural effusion: something (liquid or some kind of gunk) between my right lung and the pleural lining. This reduces my lung capacity by 10%-20%. My doctor says it will eventually dissipate, but it sure is taking a long time. I do notice that I have non-infectious pneumonia-like symptoms. There’s occasional slight pain, and I sometimes get a little short of breath and get tired a bit more easily than I’d like. But I don’t generally notice theses symptoms. Compared to how I felt six weeks ago, I’ll take what I’ve got.

How Did This Happen?

Okay, so how did all this happen? What was the cause of the Streptococcus milleri liver infection in the first place?

As I mentioned, this is a bacterium that we all have in our mouths, stomachs and intestines, but it’s toxic in the bloodstream. My team of infectious-disease doctors were hardcore medical detectives. They were extremely inquisitive about my travel, activities, diet and dental history. One doctor in particular kept asking me about recent dental work. Yes, I’d had a cleaning by a dental hygienist, and I got a new crown during the summer, but that didn’t seem to be it. I had to think back. What happened in the April-May timeframe of when this might have started.

And then it occurred to me. Back in the spring, my hygienist convinced my to start using a Waterpik in addition to flossing, and I did so every day. But there was one area of my gums that always bled. If I’d read the instructions for the Waterpik, I’d probably have found they said something like, “If your gums bleed, stop.” But I just figured I needed to toughen up those flabby gums, so I kept using the Waterpik on them night after night. Every night they bled. And every night that opened a pathway for more Streptococcus milleri to enter my bloodstream.

We’ll never know for sure. The evidence doesn’t give us a provable cause-and-effect relationship, but the circumstantial evidence is so strong, that I and my doctors are satisfied that my constant traumatizing of my gums was the ultimate cause of my live abscess. Not surprisingly, my Waterpik was swiftly and unceremoniously disposed of once I got home.