Why Luminosity? Without variations in brightness (tonality) a black-and-white image would be nothing more than a solid gray rectangle. But the same concept applies to color images as well. Without luminosity you wouldn’t be able to see the folds in a piece of fabric or the shape of a mountain. There would be no way to distinguish the light and dark areas of the same color. Luminosity, more so than color, is the key to defining shapes and showing detail in an image, b&w or color.

I’ve been on a three-year quest to understand how best to manage luminosity, particularly in Photoshop. My goal in Part 1 of this article is to explain what I’ve learned along the way towards my current luminosity workflow. Yes, I could simply jump to my current techniques, which I will instead cover in Part 2, but I think the evolution and order of presentation is important to developing a clear understanding of how the more advanced techniques work and how and when they should be used. Sorry to be such a tease, but I think you’ll thank me in the end.

I’ve pulled together these tools and techniques for managing and improving luminosity from a variety of sources. Almost none of them are of my own invention, and even those I thought were so clever turned out to be invented by someone else long before.

Although I’ve included a few examples and even some step-by-step moves, rather than describe every tool and technique in detail, I’ve opted wherever possible to link to a webpage or video that explains the technique better than I can do within the scope of this article.

Note: This article is based on my presentation to the Marin Photo Club’s Advanced Photoshop SIG in March 2013. Special thanks to Scott Loftesness for discovering and researching many of the techniques and resources described here and for providing feedback at various stages.

The Big Picture: Where Does Luminosity Adjustment Fit in the Workflow? After correcting camera/lens issues (chromatic aberration, distortion, white balance) and recovering highlights and shadows in Adobe Camera RAW (ACR), Lightroom, etc., the next step is to work on an image’s luminosity. This is true regardless of whether it’s a color or monochrome image. In other words, luminosity adjustment comes right after initial RAW processing of an image either in Lightroom or ACR.

Hierarchy. Instead of grouping techniques according to the problems they solve (e.g., putting all the highlight-recovery techniques together), I’ve organized them according to the complexity of the concepts that underlie the techniques. The sequence is also more-or-less the order in which I learned the techniques as I’ve delved deeper and deeper into Photoshop and learned from the gurus of luminosity.

Below is an outline of those increasingly sophisticated concepts. These are not steps in a workflow. They’re just categories of different ways to understand and solve the same problems of adjusting the luminosity of an image. Over time, as your Photoshop skills improve and you learn more about these techniques, you’ll find you’re drawn to using those in the categories farther down the list.

Starting with the most basic, here are the techniques for dealing with image luminosity:

- Global Adjustments. Alter the entire image using direct image adjustment or adjustment layer (e.g., Brightness/Contrast, Curves)

- Local Adjustments. Use an adjustment brush (e.g., the Dodge and Burn tools) or a similar tool to affect only part of the image.

- Global Adjustments with Masks. Use a global adjustment to alter the entire image, but control which portions are affected using a layer mask. The mask might be:

- a manually created selection (affects specific areas)

- a channel used as a mask (affects areas according to color and luminosity)

- a luminosity mask (affects areas according to luminosity regardless of color)

- Luminosity Replacement. Generate a new luminosity (layer or channel) using techniques such as:

- use one channel (e.g., red, green or blue) to redefine the luminosity of all colors;

- use one or more channels to redefine the luminosity of the image, selecting the areas, ranges or luminosity values affected using masks; or

- creating a separate monochrome version of the image and using that to redefine the luminosity of the color image.

- Luminosity Painting. Use any of the above techniques to create an enhanced luminosity layer, but apply that layer by brushing with an active selection (based on yet another channel/mask) to control where the effect is applied. I’ll explain luminosity masks and luminosity painting in Part 2 of this article.

Seeing the Luminosity. To view the luminosity of an image — we’ll assume for the rest of this discussion that we’re working with a color image — here are three techniques:

- Desaturate the image. Image->Adjustment->Desaturate (⌘-shift-U on Mac).

- In the Channels palette, look at each of the RGB channels separately (⌘-3,4,5 on Mac).

- To see all ten usable channels (RGB, CMYK, Lab) get the Channels Power Tool (€20, highly recommended). The CPT plugin also simplifies applying channels to layers and masks, which we’ll use in later techniques.

The images below illustrate the before/after effect of the Desaturate command. Notice how similar the previously blue and yellow areas appear because they have very similar luminosity values. Also note that the number “1” on the hull is nearly invisible because it has almost the same luminosity value as the area immediately around it.

The four images below illustrate the contents of the individual color channels. Note, for example, how much difference there is between the blue and yellow areas in the B channel. Yellow is the complement of blue and hence appears very dark in the B channel. Also note how the number “1” on the boat’s hull appears much more clearly in the R channel than in the other color channels or the full RGB image. We’ll look at ways to use the R channel to enhance that detail in the color/RGB image later in this article. (Mark Lindsay’s Channeling Channels is a good introduction to the concepts of channels.)

Global Luminosity Adjustment Tools. Photoshop includes a number of tools in the Image->Adjustments menu for making adjustments to luminosity of the entire image. You may have thought they were too simplistic to bother with, but you should become familiar with each of them. There are many situations in which they’re more valuable than you might expect, particularly when manipulating masks. The same or similar tools are also available as Adjustment Layers, which is the preferred way to use them in most cases since Adjustment Layers are non-destructive. I generally only se the menu-based adjustments to increase the contrast of a layer mask — something I can easily restore if I’m not happy with the results.

- Brightness/Contrast

- Curves

- Levels

- Exposure

- Shadows/Highlights

- Threshold (sometimes useful in mask manipulation)

Below is a before/after example of a global luminosity adjustment (a Levels adjustment in this case).

Local Luminosity Adjustment Tools (Dodge & Burn). Dodging and burning are techniques every photographer should learn. As opposed to global changes in contrast and exposure, these local adjustments are where you really learn to producer richer images with more depth and detail. They’re also the basis for the most advanced technique we’ll cover in Part 2, luminosity painting.

There are a variety of ways to selectively dodge (lighten) and burn (darken) specific areas of an image. The simplest are the Dodge and Burn tools that have been a part of Photoshop for many years.

The Dodge and Burn tools are destructive, so before using them make a copy of the layer you want to adjust. The only way to reliably reverse the effect of these tools in their normal use mode is to use the Undo command. An advantage of these tools, however, is that you can elect to alter only the highlights, midtones or shadows of an image using a pull-down in the tool’s property area.

For example, if you dodge an area of high contrast that has both light and dark areas, the light areas will be lightened while the dark areas will be far less affected. Hence the contrast will be increased.

As we look at increasingly more powerful techniques, we’ll see better and better ways of dodging and burning your images.

Consider Working in Lab Color Mode. When working in the RGB colorspace, particularly when making substantial adjustments, increasing contrast using the above tools has the unwanted side effect of also increasing color saturation.

There are two solutions to this problem. The first (and my preference) is to use these tools in Lab color mode in which you can adjust the L channel (Luminance) independent of the a & b (color) channels.

Rather than convert your entire image to Lab (and possibly mess up some of the adjustments you’ve already made), use Image->Duplicate… and select Duplicate Merged Layers Only. Then convert the copy to Lab mode (Image->Mode), make your adjustments, merge the layers, and finally copy the Lab image onto the RGB version. The Lab image will appear as a new layer, which you can then temper with the Opacity adjustment.

Sidebar: Copying Images as Layers. A few students have told me they didn’t know how to copy one image onto another as a new layer. I couldn’t locate a short video on this topic, so here are the steps in longhand.

- To start, your images must be exactly the same size (in pixels).

- Enable the Move tool (keyboard shortcut: v).

- Hold down the shift key, which tells Photoshop you want the source image to be aligned with the target image.

- If you’re in tab-view mode, drag the source image to the destination image’s tab, but don’t release either the mouse button or the shift key. Wait for a moment for the destination image to appear, then continue dragging into the destination image itself. Release the mouse button and the shift key.

- If you’re in a tiled-view mode, drag and drop the source image to the destination image, then release the shift key.

For example, the left image below is the original. The center and right images show the results of Levels adjustments of gamma=0.35. The center one was done in RGB mode and illustrates the increased saturation. The right image was done in Lab mode and demonstrates that only the contrast has changed.

The Lab color mode is an extraordinarily powerful tool but beyond the scope of this discussion on luminosity. For more information on using Lab color, start with my post on Lab Color and My Workflow du Jour.

Get to Know Blend Modes and Blend-If. From here on, you should be comfortable with both blend modes and the blend-if options in Photoshop’s Layer Style dialog box. I’ve previously written an article on Blend Modes in Photoshop that should get you started.

Dodging and Burning with Blend Modes. Once you understand blend modes there are better ways to do almost anything when it comes to luminosity in Photoshop. Blend modes give us two better ways to do dodging and burning.

The first variation is to make your adjustments on a new layer in Overlay (strong) or Soft Light (weaker) blend mode filled with 50% gray. The advantage is that you can undo your dodging and burning either by using the Eraser tool or by painting with a 50% gray brush. The disadvantage is that you’ll no longer have the option of selectively altering the highlights, midtones or shadows.

The second technique is to paint with a black or white brush on a 50% gray layer set to Overlay or Soft Light blend mode. This has the same strengths and weaknesses as using the Dodge and Burn tools. I recommend two videos on this technique, both of which will also lead you to a slew of other great videos: Aaron Nace’s Dodge & Burn, and Sean Bagshow’s Dodge & Burn. If you’re new to or uncertain about blend modes, these videos will help.

Highlight/Shadow Recovery (Blend Modes). Another simple technique using blend modes is to enhance the brightest and darkest areas of your image.

You can’t truly recover blown-out highlights (or plugged-up shadows) with Photoshop, but you can to some extent darken (lighten) and increase the contrast in those areas to show more detail. (If your original image is in RAW format, you can recover at least some of the highlight and shadow information, but you need to do that in your RAW processing software — Lightroom, ACR, etc. — before bringing your image into Photoshop.)

To darken highlights, duplicate the background layer, then change the blend mode of the top layer to Multiply. This will darken everything, so go into Layer Styles and use the This Layer blend-if sliders (aggressively!) to restrict the darkening to only the highlight areas.

To lighten the shadows, do the same as above, but use Screen mode instead of Multiply and use blend-if to keep the effect out of midtones and highlights.

The four images below illustrate how these techniques can be used separately and together.

Masks and Selections. The above examples of highlight and shadow recovery were created using only blend modes and the blend-if feature. But to combine the recovered images into the final “Both” version I had to use a layer mask filled with a gradient. That’s because I couldn’t create a smooth transition of the midtones in the image (the background mountains and some of the red soil in the foreground) using blend-if.

You’ll frequently find that using continuous-tone masks such as gradients and masks created from the color channels (e.g., the red, green and blue channels) are very helpful in isolating the effect of your adjustments to specific areas or tones within an image. We’ll see much more about this in Part 2.

Because so much detail is contained in the luminosity of an image, you’ll likely find the traditional means of creating a selection or mask (e.g., the lasso tools, the quick selection tool and the magic wand) are far less helpful than you might expect. These tools create all-or-nothing rather than continuous-tone selections, and even if you try to adjust or soften their edges (e.g., using Refine Edge), you often don’t get what you want.

In Part 2 we’ll explore many opportunities to use color channels as masks. Not only are channels continuous-tone, they’re also self-feathering, guaranteeing smooth transitions between selected and non-selected portions of your image.

Furthermore, hard-edge selections create masks that contain no detail except at their edges, whereas masks made from channels retain all the detail from that channel.

Get to Know Channels and Apply Image. The techniques described in the remainder of this article require that you copy images or channels to layers or masks. There are a number of keyboard shortcuts, but they’re hard to remember and not very flexible. The fundamental tool for copying images or channels to other places is the Image->Apply Image… dialog box.

I suggest you read Harold Davis’ Using Image Apply Image on photo.net. Don’t be scared off by the length of the article. Alternatively you can search the Internet for Photoshop Apply Image Video to find many video tutorials on the topic.

Luminosity Enhancement Using Channels. The objective of luminosity enhancement is to bring out detail in desired areas of an image. Bringing out detail generally means increasing contrast within those areas, for it’s contrast that allows us to see detail.

Unless an image is strictly black-and-white, there is always more contrast in one of the color channels (R, G or B) than in the image overall. The most basic of the luminosity enhancements techniques is to replace the overall luminosity of the image with the luminosity of the color channel that has the most desirable contrast and therefore detail (using the Image->Apply Image… dialog as shown above).

The following channel-replacement technique is recommended by many of my personal Photoshop gurus: Mark Lindsay, Lee Varis and Dan Margulis. A good way to learn more is to start with Lee Varis’ free 10-Channel Workflow videos (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4). Part 2 deals specifically with the steps to perform this enhancement:

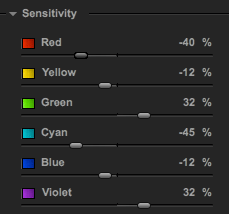

- Open the Channels palette and select the best channel. That’s best in terms of contrast in the area you want to enhance. If you have the previously mentioned CPT plug-in, you can use it to generate a preview of not just the RGB channels, but also the CMYK and Lab channels.

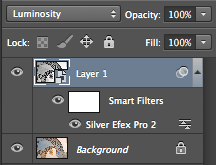

- Add a new empty layer and change its blend mode to Luminosity.

- Use Image->Apply Image… (or the CPT plug-in) to load the new layer with the selected color channel.

- For even more detail, use a Curves or Brightness/Contrast adjustment to increase the contrast in the desired area.

- Optionally, if you want to restrict the enhancement by color and/or luminosity, use the blend-if sliders in the new layer’s Layer Styles dialog box.

- As a last resort, if you want to restrict the enhancement to a specific area, you can generate a layer mask. Using the bend-if method is preferred because it can be feathered, whereas creating a mask using selections often causes undesirable hard edges.

- Note that if you’re working in the Lab colorspace, you can simply replace the L (luminance) channel rather than generate a separate layer in Luminosity mode.

The before/after images below illustrate the effect of using the red channel as the source for the luminosity layer in Lab color mode. Note that the “1” on the hull is much more clearly defined. The blend-if sliders were used to reduce the contrast increase in the blues, and this could be carried further using more of the techniques described in Lee Varis’ videos.

Doug’s Luminosity Shortcut. Although I cut my luminosity teeth on the channel-replacement techniques recommended by Varis, Lindsay, Margulis and others, I’ve pretty much switched to a simpler, quicker and in some ways more-powerful technique. I arrived at this technique by asking myself, “If the best luminosity for a color image is a good black-and-white image, why not just use the best tool for making b&w images?”

My personal favorite b&w tool is Nik’s Silver Efex Pro 2, and I’ve described the method of using that plugin for managing the luminosity of color images in Silver Efex Pro for Color Images.

Luminosity Masks and Painting. It was less than four months ago that I published Lab Color and My Workflow du Jour, an article whose title suggests that I’m quite frequently changing how I process images. While I’m still using some of the du Jour techniques and the Silver Efex Pro shortcut as appropriate, I now find I’m more often using another workflow based on luminosity masks. I find them to be extremely powerful, and once mastered, there quite easy to use.

To Be Continued. In Part 2 of this article I’ll explain the next level of luminosity adjustment techniques: luminosity masks and luminosity-mask painting, both of which I first learned from Tony Kuyper. If you can’t wait, see Tony’s articles on Luminosity Masks and Luminosity Painting.